Lauren Diehl and Aidan Bodner from Simon Fraser University explore how US border control impacts upon the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March 2020, the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ordered the implementation of Title 42 – providing the executive branch authority to prevent the entry of “persons or property” from a country where there is a threat of introducing a communicable disease to the US. Despite being framed as a public health order, Title 42 has been used to restrict migrant movement across the US-Mexico border, violating rights to asylum and non-refoulement. Under Title 42, migrants have been refused entry, resulting in increased threats to public health due to unsafe and unsanitary conditions along the border.

Title 42 has exacerbated human rights violations at the border, both Mexican and US governments do not offer sufficient assistance to keep migrants safe. Decades-long increases in rates of violence – particularly in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador – has driven hundreds of thousands of migrants to arrive at the US-Mexico border annually. Women, children, and LGBTI people are disproportionately impacted by this violence and currently, there is little to no state monitoring, prosecution, or interventions targeting violence against these populations.

In using COVID-19 as justification to operationalize Title 42, the Trump Administration applied political pressure on the CDC to authorize the restriction of entry at land ports to the US for undocumented people. This was premised on reality that most migrants arriving at land ports of entry do not possess sufficient documentation. Furthermore, it was reasoned that the processing capacity of US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) would likely not be adequate to meet a large demand for migration processing and COVID-19 infection control, raising the possibility of transmission into the US.

The CDC’s cut back on the processing of undocumented migrants uses the public health rationale provided by Title 42. But while the statute was intended to give power to compel the quarantining of people or property, there is no legal precedent of its application for deportation purposes. This also contradicts the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which includes the right to apply for asylum, and the Refugee Act of 1980, which prevents individuals seeking asylum from being returned to a place where they would be harmed; and mandatory protection from torture. The order justifies the turning away of migrants who may be seeking asylum and does not ensure safety in Mexico. Moreover, the public health reasoning used to prop-up the order is dubious, as it is based on an assumed and not case-by-case assessment of risk by CBP; it does not speak to the organization’s capacity to apply more resources to ensure safety.

Previous policies to prevent immigration have resulted in thousands of migrants being forced to endure long processing times at the border and resulted in many migrants taking remote and dangerous routes to avoid this. In turn, it has produced precarious situations for migrants denied entry to the US as a result of Title 42, pushing them to make-shift shelters (forcing migrants into an endless state of travel), homelessness, or return to their place of origin. This has created an environment where expelled migrants, particularly women, children and LGBTI people, are being targeted by gangs, sexually assaulted, separated from their families, or even murdered. Moreover, migrants in camps are largely reliant on civil society’s efforts for food, water, and other humanitarian aid.

Recommended Next Steps

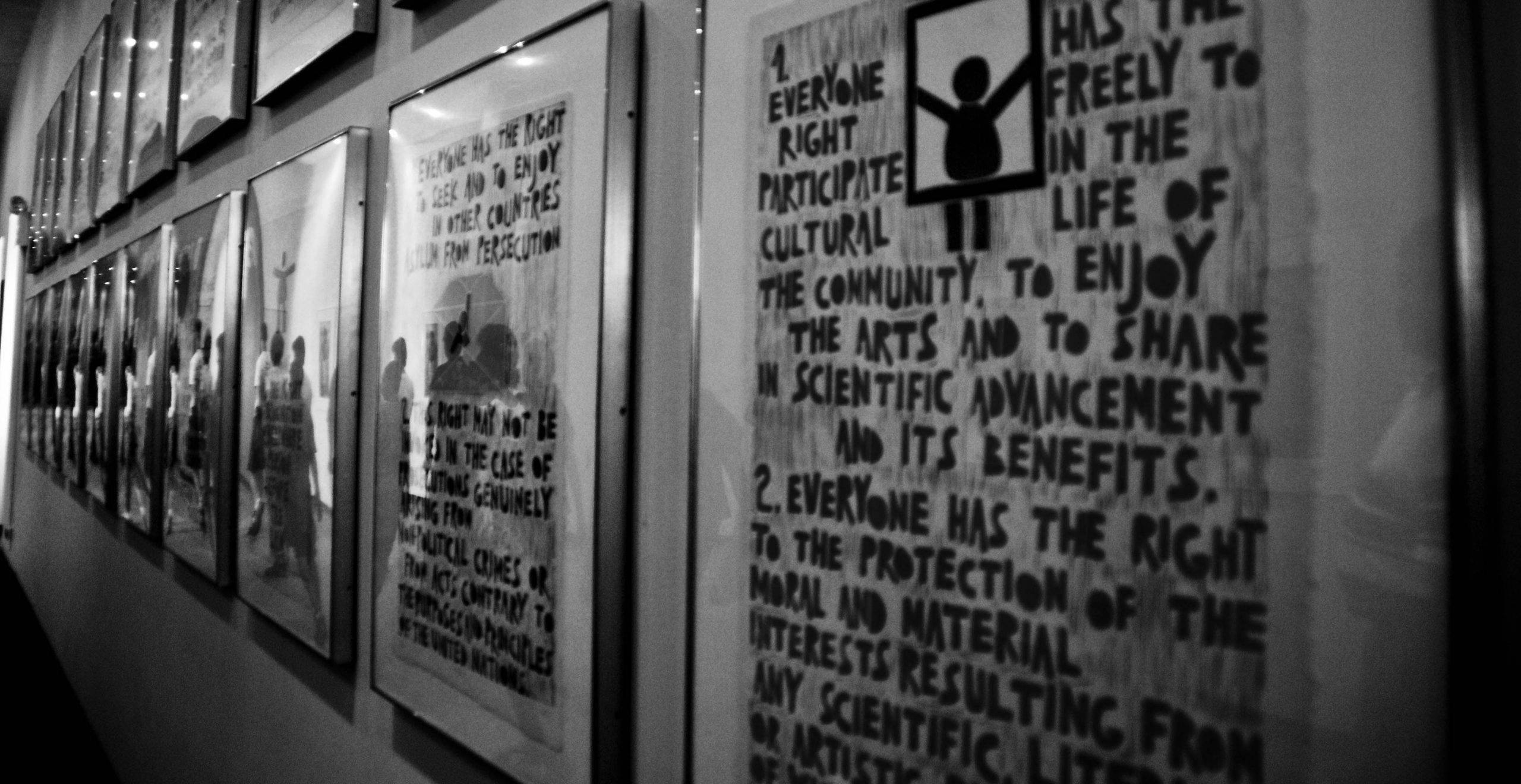

While the current response to the situation at the US-Mexico border by the US, Mexico, and international community has lacked state-backed solutions and shouldered the responsibility of protecting human rights on civil society, the Global Compact for Migration offers guidance for potential community- to government-based solutions. Similarly, the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) outlines key provisions with respect to “security of person”, protection from torture, fair legal process and “protection from discrimination”, “seek[ing] other countries asylum from persecution”, and “adequate food, clothing, housing, and medical care”.

- The Title 42 order must immediately be lifted so that asylum claims can be processed with appropriate COVID-19 protocols in place

- As a signatory to the UNDR, the US has an obligation to course-correct its harmful migration stance

- The US government must support humanitarian organizations that are currently leading in assisting migrants at the border

- Implementing measures to ensure the continued provision of food, water, sanitation, and housing for migrants approaching the border as well as the assured security of migrants, including protection from gender-based violence at the border is needed through bilateral support and action from the US and Mexico

Steps should be taken to minimize future potential for political interference in public health:

- This could include a rapid review of major policy directions that the CDC wishes to pursue by the House Committee on Oversight and Reform as outlined in House Rule X, clause 2(b). This would allow for a bipartisan review and check of the executive branch (i.e., the CDC)

Tackle the adverse drivers and structural factors that compel people to leave their country of origin:

- As a global leader in providing foreign aid, it is imperative that the US assist countries who send many migrants and address social and political conditions that create turbulence in their home countries. As outlined in Objective 2 of the Global Compact for Migration, active investment in employment and educational programs that empower people, particularly women, children and LGBTI individuals are key to these interventions

- The US should move towards engaging in multilateral dialogue promoting commitments to fair governance, gender equality and human rights among its global partners within countries such as Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador as a means to address key push-factors driving migrant travel to the US-Mexico border