Research, supported by the Alberta Teachers’ Association and led by Dr Julia Smith of the Gender and COVID-19 Project, centers experiences of 29 female teachers and school leaders. It reveals the adverse effects of the pandemic on the well-being of educators as they worked towards sustaining the education sector in a time of chaos and uncertainty. Alice Mũrage gives us the highlights.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to remind us of the importance of childcare to the economy. Working parents have had to take time off work or reduce their productivity to take care of their children in times of school closures and interruptions; an opportunity cost mostly borne by mothers. In Canada, women do up to three times the amount of unpaid care work of men. While this secondary effect of the pandemic has received attention in public, academic, and policy circles, the experiences of educators, whose labour is critical in this equation, remains unappreciated.

The education sector is highly feminized, and over 70% of Alberta’s teaching professionals are women. Educators’ gender roles affected their experience both at home and at work; they were caregivers in both settings. At home, childcare needs increased, particularly when their children’s schools or childcare centers were closed or when their children needed to self-isolate. At work, emotional labour increased as educators tried to create an environment of calm and normality by meeting emergent emotional needs of both students and co-workers. This was in addition to increased workload resulting from staff shortage, implementation of COVID-19 protocols, and adjusting teaching methods.

A teacher illustrated the severity of emotional needs that characterized their daily work by sharing how a student expressed suicidal thoughts in one of her virtual classes. As educators exerted themselves to meet increased emotional and learning needs of their students, they found it challenging to balance competing needs at home.

“We’re expected to bring the calm everyday, but there is chaos going on in our lives and in our home…you just feel like you’re keeping all the ball in the air at one time.”

“It will take me quite some time to get over the wrongness and the guilt of not parenting my own kids in the height of the pandemic.”

85% of focus group participants described their work-life balance as either more difficult to manage or nonexistent compared to pre-COVID times. This balance was harder to strike for school leaders. Principals and vice-principals were points of contact for teachers, students and families, and responsible for contextualizing and communicating COVID-19 protocols and conducting contact tracing in case of outbreaks in schools. Consequently, they were always on call; they received calls into the night and over the weekend when there was need for contact tracing or reassignment of responsibilities or search for a substitute teacher whenever a teacher needed to self-isolate. They worked under high pressure and felt scrutinized on whether they were doing enough.

“(The) perceived community pressure that you’ll do everything you can to keep them safe means that if somebody ends up not safe, it must be your fault. And that’s a heavy load to carry.”

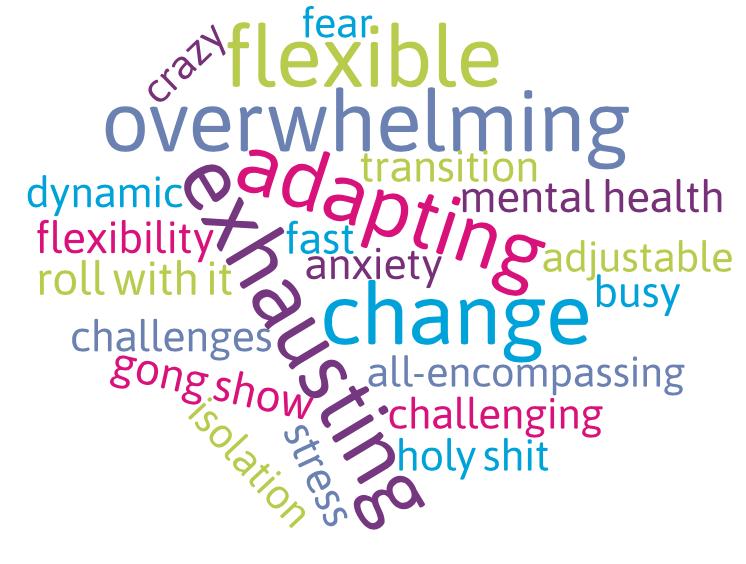

The physical and mental health of educators deteriorated as a result of burnout, anxiety, and the constant worrying. Despite the sacrifices they made to sustain the education sector, educators did not feel seen or heard. Lack of practical support and comprehensive leave policies accounting for their current realities, and not being prioritized on access to vaccination manifested as evidence of their invisibility.

“We’re just expected to know all the things that we need to do and do them, but we don’t have any real support.”

By sharing their experiences, educators hoped to make their experiences more visible. Additionally, they offered recommendations to improve their working conditions. They recommended a holistic approach that catered to their practical needs such as on-site childcare, in-school mental health support, increased flexibility, and reduced demands on extracurricular activities. Educators noted that increasing the diversity of those in decision-making spaces would result in more equitable policies which are based on lived experiences. They also highlighted the importance of inclusion through meaningful engagement.

The pandemic is still ongoing and cases in schools are on the rise. This is an important moment to reflect on the experiences of educators, appreciate their labour and sacrifices, and develop policies that support them to navigate these challenging times we find ourselves in. Now we know; we can do better.

–

The author of this blog supported the facilitation of focus group discussions with the Alberta educators.

The full report ‘COVID-19, Caregiving and Careers of Alberta Teachers and School Leaders’ is accessible HERE.